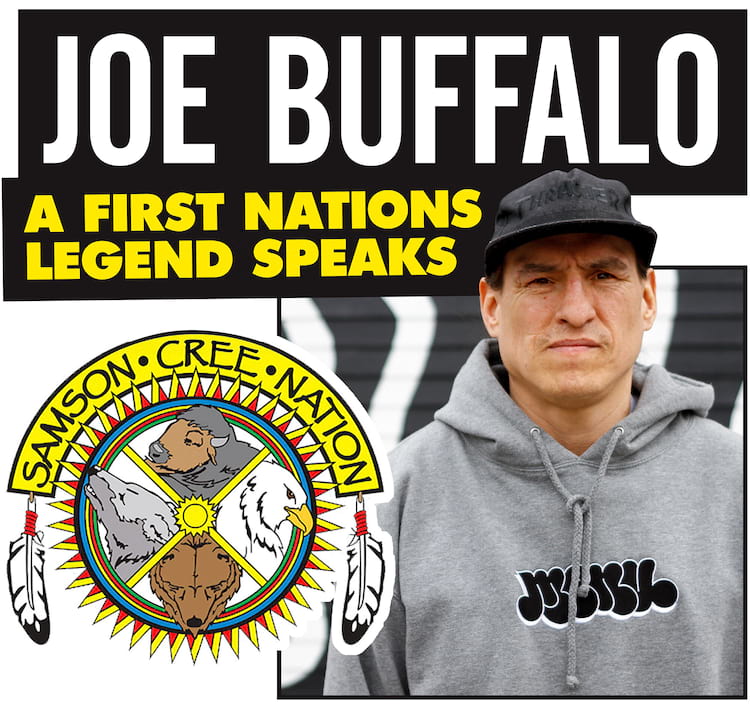

Joe Buffalo: A First Nations Legend Speaks

1/21/2022

A PROMISING young am throughout the ’90s and ’00s, Joe Buffalo’s skateboard prowess coupled with his larger-than-life character established him as a fixture within the Canadian skate scene. Unfortunately, Joe retreated from the spotlight and into the darkness of addiction, due in no small part to the intergenerational trauma inflicted on the indigenous population of Canada by racist government policies. Joe is a survivor of the residential school system, which is widely recognized as a form of cultural genocide. These schools were run by the Roman Catholic Church and funded by the Canadian government with the aim to “Kill the Indian in the child.” From the 1880s until 1996, over 150,000 aboriginal children were separated from their families and placed in residential schools where they were denied the right to practice their culture or speak their own language, as well as subjected to widespread physical, mental and sexual abuse. This system is a major factor in the disproportionate rates of addiction, suicide and incarceration which afflict Canada’s First Nations today. Now, at age 45, Joe has conquered his demons and is skating with the vigor and skill befitting a man half his age. Sober and with a recently released pro model on Colonialism skateboards, he is back to stoke a fire that was always smoldering in the shadows. We caught up with Joe to talk about growing up on the reserve in Alberta, the heyday of the street skating scene in Ottawa and Montreal and how he managed to pull himself out of a path towards self-destruction. —Stepan Soroka

As seen in the October 2020 issue

Back tail above some unforgiving Canadian crust. / Photo: James

Back tail above some unforgiving Canadian crust. / Photo: James

How would you describe life on a reserve to someone who has never visited one before?

It’s isolated and desolate. You’re living in pretty impoverished ways. On my reserve, there is a lot of oil underneath the land. So what the government did was they gave us money every month up until you turned 18. Then when you turned 18, you got this oil trust fund of $100,000. At that age, you don’t know how to fuckin’ budget money and you’ve never earned an honest dollar in your life. So that was a smart move on the government’s part to try and wipe out my people. Pre-Contact, we didn’t have a monetary system. The sole purpose of owning something was just to give it away. The government throwing money in my people’s pockets like that, it was a strategic move. Now greed is what is killing my people. In the beginning, everyone had everything they could have ever dreamed of or wanted. But as quick as they were getting that money was as quick as they were killing themselves. Sure, you’ve got that $50,000 truck, but once the money runs out you’re selling that truck—if you haven’t rolled it yet, you know what I mean? I’m still proud to say that I’m from there, but now it’s overrun by gangs, drugs and crime. It’s a pretty rough place now, man. But it is still a vibrant and active place and the youth is continuing to strive in sports and academics—it’s just the ripple effects of abuse and trauma that the government has had on my people since contact. It’s really disturbing and hard to just get over.

If you wanted to go skating while you were in residential school, could you just take off and go do it?

No. I would either have to skate in the parking lot or go AWOL, just fuckin’ run away. Regina was the closest city and I had homies there. I had to hop on a train. If I didn’t get caught on my way to Regina, they had people there looking for me. Sometimes I’d last a weekend, other times I wouldn’t even make it there. It was the raddest shit because it felt like, You’re not holding me down, you know what I mean? At the same time, I was considered an athlete so I was an asset to the school and I could get away with bending the rules.

How did sponsorship come about for you?

Eventually I became of age to pull myself out of residential school. I didn’t tell my dad I was doing this. I already had scouts’ attention for the WHL. Once my dad did find out, he was fucking crushed. It got to the point where my dad was beating up other dads on the opposing teams. The joy of scoring goals or whatever, it got outweighed by the seriousness and the dark side of hockey. Then I moved to Ottawa. I was there for about a year and a half and didn’t skate. I ran with a bad crowd and was doing hood shit. I still had a chip on my shoulder because, where I came from, I was raised to hate the white. So I was just rolling with minorities and these guys liked to beat up skaters. I ended up going to this Boys and Girls Club and in the basement they had a halfpipe and a spine. I walked in and the first thing I saw was Rick McCrank doing blindfolded blunt fakies back to back by himself. I ended up riding for the shop in the basement of the Boys and Girls Club. It was called SK8 City.

Did you ever feel unsafe skating there?

Sometimes. Once when I was hanging out there was this native guy who was obviously from where I’m from. He was wasted and just wanted confrontation. He started dancing at me with his dukes up and I wasn’t having it. I just hoofed this guy in the balls so hard and he fell over. I thought it was hilarious. I’m skating away and I look back and the dude had ripped a street sign out of the ground and was chasing me. I look over and right on Saint Laurent are some homies of mine—Mike Johnston and Jake Cain—in a BMW with the top down. They saw the whole thing go down and are like, “Buffalooo!” I jumped in the moving vehicle and escaped this dude chasing me with a sign. Those guys saved my life ’cause that guy would have fuckin’ killed me. But that was his way of reaching out—trying to act tough. The same as when you’re in a foreign country and you see someone who is from the same place as you, you want to connect with them.

At what point did you realize that partying had become a problem?

Seeing how partying was sold to the kids through skateboarding, I was like, Okay, this is normal. Having a six pack and blazing a joint per session was normal. And that just escalated as life went on, especially if you have an addictive personality like I do. You’re going to want the best of the best at all times. Before you know it, you’re out of coke and you’re smoking crack and doing heroin because there is no crack. That’s how bad it gets.

As of now, how long have you been sober?

I’ve been sober for two-and-a-half years. It wasn’t easy. I needed a support system. I didn’t do it through the fellowship or rely on a higher power, as they say. I went to ceremony and dug in into my culture and that helped heavily. The ceremony I participated in was a sweat lodge. They are a place of healing and prayer to the creator. I never did detox or rehab of any sort in order to sober up. It was mainly just sweating with the elders.

Did you notice a big change in your skating once you sobered up?

For sure. Because of how resilient and rich my blood is already—if I can survive all of this stuff the world has thrown at me, imagine if I could apply myself fully to do something? That’s what my new buzz is. It’s like my new addiction, being in control of my shit.

Can you tell us about Nations?

Nations is a non-profit that reaches out to indigenous youth through skateboarding. The squad consists of myself, Rose Archie, Dustin Henry, Tristan Henry and Adam George. Our first gig was going to Fort St. John in northern BC. Vans was on board and gave us 50 pairs of shoes and we had a non-profit here that helped us out with some set-ups. We had 44 kids up there and each one of them got a set-up and a pair of shoes. When those kids came in, none of them had ever stepped on a skateboard. When we were done they were lining up to drop in on the quarterpipe. That’s how quick they took to it. It got to the point where our job was done. These kids are legit just shredding now.

How do you feel about the current state of indigenous skateboarding?

I feel like it is at an all-time high because of the popularity of skateboarding right now. Back when I started, indigenous/First Nations skaters were few and far between and I didn’t even know a scene existed anywhere else. One exception was Sam Devlin who had a part in Trilogy. Back in the day you could get your ass kicked just for having a skateboard anywhere you went. You were labeled an outcast. Now everyone and their dog skateboards, and I’ll bet that it is only going to continue to grow from here.

For more info check: @nationskateyouth

Back tail above some unforgiving Canadian crust. / Photo: James

Back tail above some unforgiving Canadian crust. / Photo: James Where were you born?

I was born in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, on June 7th 1976. I went to the reserve not long after I was born. So I am Cree from Samson Cree Nation, from Maskwacis, Alberta.

I was born in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, on June 7th 1976. I went to the reserve not long after I was born. So I am Cree from Samson Cree Nation, from Maskwacis, Alberta.

How would you describe life on a reserve to someone who has never visited one before?

It’s isolated and desolate. You’re living in pretty impoverished ways. On my reserve, there is a lot of oil underneath the land. So what the government did was they gave us money every month up until you turned 18. Then when you turned 18, you got this oil trust fund of $100,000. At that age, you don’t know how to fuckin’ budget money and you’ve never earned an honest dollar in your life. So that was a smart move on the government’s part to try and wipe out my people. Pre-Contact, we didn’t have a monetary system. The sole purpose of owning something was just to give it away. The government throwing money in my people’s pockets like that, it was a strategic move. Now greed is what is killing my people. In the beginning, everyone had everything they could have ever dreamed of or wanted. But as quick as they were getting that money was as quick as they were killing themselves. Sure, you’ve got that $50,000 truck, but once the money runs out you’re selling that truck—if you haven’t rolled it yet, you know what I mean? I’m still proud to say that I’m from there, but now it’s overrun by gangs, drugs and crime. It’s a pretty rough place now, man. But it is still a vibrant and active place and the youth is continuing to strive in sports and academics—it’s just the ripple effects of abuse and trauma that the government has had on my people since contact. It’s really disturbing and hard to just get over.

Was it difficult to get boards, shoes and skate stuff where you were living?

At the beginning, I didn’t know what was what. I didn’t know if a board was from Walmart or whatever—it had wheels and it rolled. There were these white kids in the town outside my reserve who skated and they were like my first sponsor. They were kicking me down their old boards, old shoes, old anything.

At the beginning, I didn’t know what was what. I didn’t know if a board was from Walmart or whatever—it had wheels and it rolled. There were these white kids in the town outside my reserve who skated and they were like my first sponsor. They were kicking me down their old boards, old shoes, old anything.

How about being exposed to the wider world of skating, were you able to see magazines and videos?

I didn’t know. I thought I made up the Smith grind. I was like, That’s my shit! No one does this. I was just so sheltered from it all. I remember lunchtime in residential school, like grade six, we were watching Shackle Me Not on the TV in the lunchroom. Some older students must have left it playing. I was like, What is this?!

I didn’t know. I thought I made up the Smith grind. I was like, That’s my shit! No one does this. I was just so sheltered from it all. I remember lunchtime in residential school, like grade six, we were watching Shackle Me Not on the TV in the lunchroom. Some older students must have left it playing. I was like, What is this?!

How old were you when you went to residential school and how long did you stay?

I went for five years, from grade six to nine and I was in grade nine for two years. Because I excelled at hockey, there were three residential schools that I could pick from. I wanted to go to the NHL. That was my dream. Well, that was my dad’s dream. So I went to the winningest school. But it got out of hand because my dad missed the boat. He never made it pro and he was living vicariously through me. These schools were put in place by the Canadian government and the Roman Catholic Church. They were used as a form of genocide to demolish my people—the same as the whiskey trade, the same as starving my people and killing off all the buffalo, as tuberculosis, as smallpox. I didn’t know about the atrocities that happened because my mom went and my grandparents went, and all my brothers and sisters went, so this was normal. I didn’t realize the severity of it and Canada’s dark colonial history. They did teach Cree, which was my native language. I was fortunate because this was in the ’90s. Back in my mom and dad’s day, they weren’t allowed to practice their language or their culture. They beat the fuckin’ native out of them. The priests used to pluck kids out of the dormitories and rape them. There was a lot of bad shit that went down. I was just there to play hockey.

I went for five years, from grade six to nine and I was in grade nine for two years. Because I excelled at hockey, there were three residential schools that I could pick from. I wanted to go to the NHL. That was my dream. Well, that was my dad’s dream. So I went to the winningest school. But it got out of hand because my dad missed the boat. He never made it pro and he was living vicariously through me. These schools were put in place by the Canadian government and the Roman Catholic Church. They were used as a form of genocide to demolish my people—the same as the whiskey trade, the same as starving my people and killing off all the buffalo, as tuberculosis, as smallpox. I didn’t know about the atrocities that happened because my mom went and my grandparents went, and all my brothers and sisters went, so this was normal. I didn’t realize the severity of it and Canada’s dark colonial history. They did teach Cree, which was my native language. I was fortunate because this was in the ’90s. Back in my mom and dad’s day, they weren’t allowed to practice their language or their culture. They beat the fuckin’ native out of them. The priests used to pluck kids out of the dormitories and rape them. There was a lot of bad shit that went down. I was just there to play hockey.

If you wanted to go skating while you were in residential school, could you just take off and go do it?

No. I would either have to skate in the parking lot or go AWOL, just fuckin’ run away. Regina was the closest city and I had homies there. I had to hop on a train. If I didn’t get caught on my way to Regina, they had people there looking for me. Sometimes I’d last a weekend, other times I wouldn’t even make it there. It was the raddest shit because it felt like, You’re not holding me down, you know what I mean? At the same time, I was considered an athlete so I was an asset to the school and I could get away with bending the rules.

How did sponsorship come about for you?

Eventually I became of age to pull myself out of residential school. I didn’t tell my dad I was doing this. I already had scouts’ attention for the WHL. Once my dad did find out, he was fucking crushed. It got to the point where my dad was beating up other dads on the opposing teams. The joy of scoring goals or whatever, it got outweighed by the seriousness and the dark side of hockey. Then I moved to Ottawa. I was there for about a year and a half and didn’t skate. I ran with a bad crowd and was doing hood shit. I still had a chip on my shoulder because, where I came from, I was raised to hate the white. So I was just rolling with minorities and these guys liked to beat up skaters. I ended up going to this Boys and Girls Club and in the basement they had a halfpipe and a spine. I walked in and the first thing I saw was Rick McCrank doing blindfolded blunt fakies back to back by himself. I ended up riding for the shop in the basement of the Boys and Girls Club. It was called SK8 City.

The Peace Park ollie champ can still blast! Over the pole and into the future. / Photo: James

And eventually you started skating at Peace Park in Montreal a lot, right?

In the early 2000s I would hear about best-trick contests at Taz Mahal in the winter. I would go to these contests and do well at them, to the point where I would have enough money to hang out for a week. The Montreal locals back then were so much more advanced at skating and super welcoming. I’d always hear about Peace Park, but because we would only go to Montreal in the winter, we never did much venturing. But once I started going to Peace Park it was habitual. I saw a lot of shit go down there. I saw a one-armed Mexican guy get stabbed to death. He was a local, never had his shirt on. He’d always be partying. He was our fuckin’ dude. One night he got into some fisticuffs. It looked like he had just gotten punched. All of a sudden we see trails of blood everywhere and we’re like, What the fuck? Are we bleeding? The homie was stumbling down the alleyway. We followed the trail and he ended up bleeding out there in the alley.

In the early 2000s I would hear about best-trick contests at Taz Mahal in the winter. I would go to these contests and do well at them, to the point where I would have enough money to hang out for a week. The Montreal locals back then were so much more advanced at skating and super welcoming. I’d always hear about Peace Park, but because we would only go to Montreal in the winter, we never did much venturing. But once I started going to Peace Park it was habitual. I saw a lot of shit go down there. I saw a one-armed Mexican guy get stabbed to death. He was a local, never had his shirt on. He’d always be partying. He was our fuckin’ dude. One night he got into some fisticuffs. It looked like he had just gotten punched. All of a sudden we see trails of blood everywhere and we’re like, What the fuck? Are we bleeding? The homie was stumbling down the alleyway. We followed the trail and he ended up bleeding out there in the alley.

Did you ever feel unsafe skating there?

Sometimes. Once when I was hanging out there was this native guy who was obviously from where I’m from. He was wasted and just wanted confrontation. He started dancing at me with his dukes up and I wasn’t having it. I just hoofed this guy in the balls so hard and he fell over. I thought it was hilarious. I’m skating away and I look back and the dude had ripped a street sign out of the ground and was chasing me. I look over and right on Saint Laurent are some homies of mine—Mike Johnston and Jake Cain—in a BMW with the top down. They saw the whole thing go down and are like, “Buffalooo!” I jumped in the moving vehicle and escaped this dude chasing me with a sign. Those guys saved my life ’cause that guy would have fuckin’ killed me. But that was his way of reaching out—trying to act tough. The same as when you’re in a foreign country and you see someone who is from the same place as you, you want to connect with them.

Was there a point when sponsorship and stuff like that started to fizzle out?

Yes, for sure. I was deep into my addiction. Losing sponsors was normal because I wasn’t skating. Sure, I had my board with me, but I wasn’t trying shit. People were approaching me for pro boards and I didn’t think I deserved it. I didn’t care and I didn’t put enough into it.

Yes, for sure. I was deep into my addiction. Losing sponsors was normal because I wasn’t skating. Sure, I had my board with me, but I wasn’t trying shit. People were approaching me for pro boards and I didn’t think I deserved it. I didn’t care and I didn’t put enough into it.

At what point did you realize that partying had become a problem?

Seeing how partying was sold to the kids through skateboarding, I was like, Okay, this is normal. Having a six pack and blazing a joint per session was normal. And that just escalated as life went on, especially if you have an addictive personality like I do. You’re going to want the best of the best at all times. Before you know it, you’re out of coke and you’re smoking crack and doing heroin because there is no crack. That’s how bad it gets.

Do you feel like your experience as a First Nations person in Canada contributed to your drug and alcohol abuse?

For sure. The loss of language and culture and not being able to practice that when you’re in residential school, it affected me heavily. Because that’s how I was raised. I was born and the next fuckin’ day I was in a sweat lodge. I was raised around culture and ceremony and you go to these institutions and you can’t practice that.

For sure. The loss of language and culture and not being able to practice that when you’re in residential school, it affected me heavily. Because that’s how I was raised. I was born and the next fuckin’ day I was in a sweat lodge. I was raised around culture and ceremony and you go to these institutions and you can’t practice that.

Was there a particular moment or event that inspired you to sober up?

I just didn’t want to be a fuckin’ statistic, man. I didn’t want to have people say, “Oh yeah, he was a rad dude but too bad he went out this way,” you know what I mean? They’ll remember you as a number. I’d much rather be remembered as the one who, despite the circumstances, went out swinging. Being in survival mode all the time, once I was finally able to let my guard down and live comfortably, that’s when I was able to channel energy and strive to better my life. I had to do a full fuckin’ inventory of every bad thing that has happened to me and every little thing that I’d ever done wrong. From there I had to decipher everything. Once I picked apart all my coping mechanisms and got to the bottom of all my unresolved childhood traumas, my chest opened up and I could breathe again. And from there I started making sounder decisions in life. I started noticing toxic behavior, little quirks that I didn’t know were there. I was sobering up and realizing that there is a life worth living. Just because the government programmed me to self-terminate through these schools that I went to doesn’t mean I have to go and do it.

I just didn’t want to be a fuckin’ statistic, man. I didn’t want to have people say, “Oh yeah, he was a rad dude but too bad he went out this way,” you know what I mean? They’ll remember you as a number. I’d much rather be remembered as the one who, despite the circumstances, went out swinging. Being in survival mode all the time, once I was finally able to let my guard down and live comfortably, that’s when I was able to channel energy and strive to better my life. I had to do a full fuckin’ inventory of every bad thing that has happened to me and every little thing that I’d ever done wrong. From there I had to decipher everything. Once I picked apart all my coping mechanisms and got to the bottom of all my unresolved childhood traumas, my chest opened up and I could breathe again. And from there I started making sounder decisions in life. I started noticing toxic behavior, little quirks that I didn’t know were there. I was sobering up and realizing that there is a life worth living. Just because the government programmed me to self-terminate through these schools that I went to doesn’t mean I have to go and do it.

As of now, how long have you been sober?

I’ve been sober for two-and-a-half years. It wasn’t easy. I needed a support system. I didn’t do it through the fellowship or rely on a higher power, as they say. I went to ceremony and dug in into my culture and that helped heavily. The ceremony I participated in was a sweat lodge. They are a place of healing and prayer to the creator. I never did detox or rehab of any sort in order to sober up. It was mainly just sweating with the elders.

Photo: James

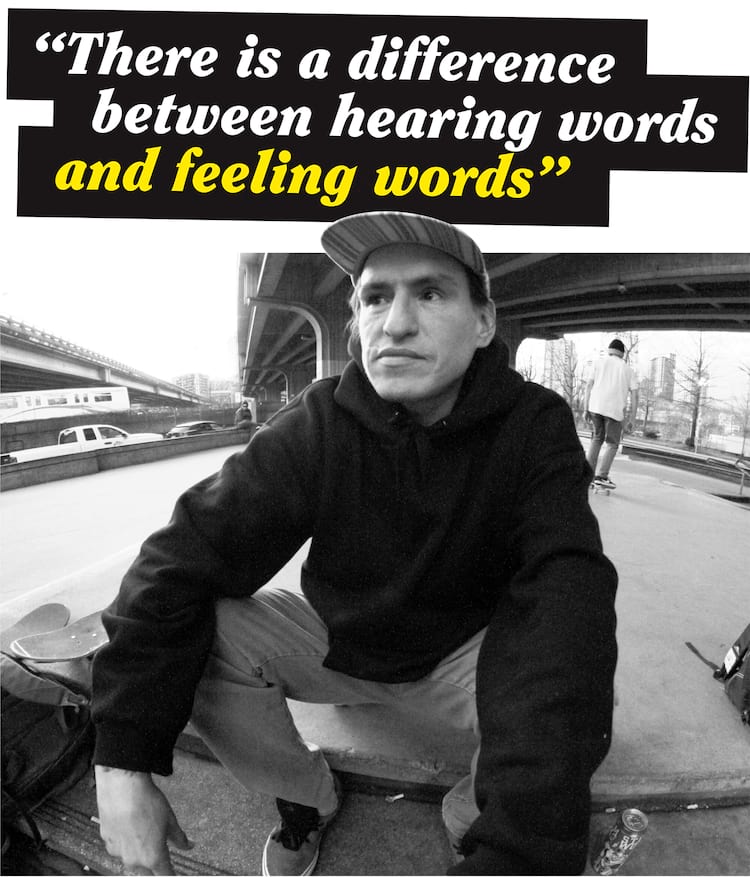

What advice would you give to somebody who is struggling with addiction?

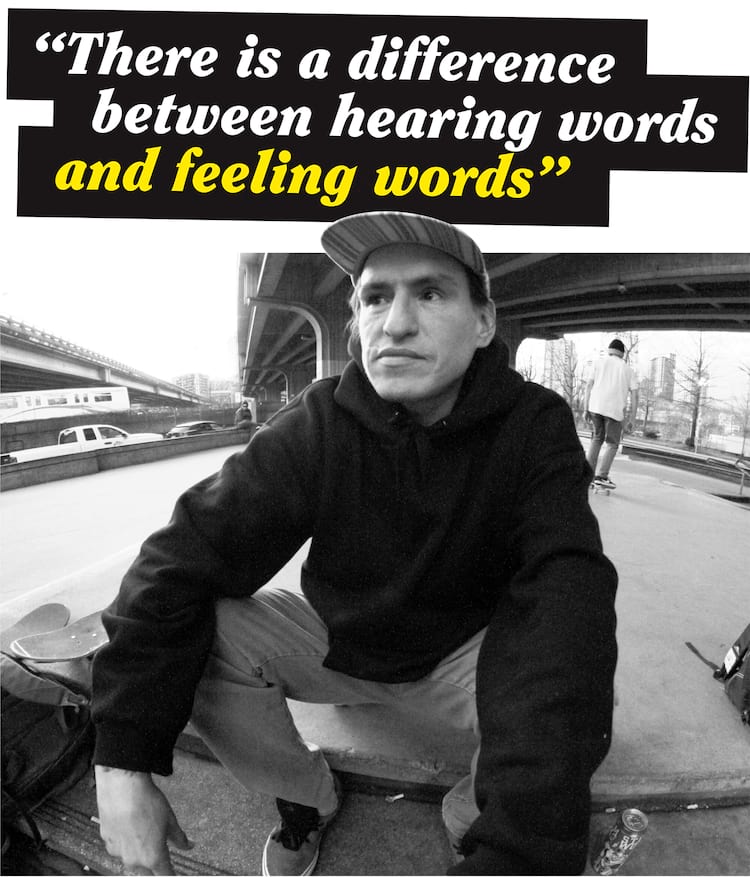

I’ve tried giving advice to people and they’ve done the complete opposite. There is a difference between hearing words and feeling words. I could be blue in the face, telling someone, “Look, man, these red flags over here are telling me you’re gonna be a mess over there.” For me, it took cheating death a bunch of times. I overdosed three times in a summer. I had already lost like ten friends in two months because of fentanyl. Everyone was dropping dead around me. I had to put an end to it all and alcohol was the whole reason for me going and looking for drugs. I’d be on autopilot going and looking for the shit. You have to remember that Pre-Contact, my people never had alcohol. That’s why my people’s bodies react differently to alcohol than, say, your people’s. That’s a factor as to why so many of my people are either dead, in jail or struggling on the streets. It’s a form of genocide that is still devastating to this day—the effects of the whiskey trade.

Did you notice a big change in your skating once you sobered up?

For sure. Because of how resilient and rich my blood is already—if I can survive all of this stuff the world has thrown at me, imagine if I could apply myself fully to do something? That’s what my new buzz is. It’s like my new addiction, being in control of my shit.

Maintaining a healthy buzz with an ollie up to tailslide. / Photo: Morrison

Can you tell us about Nations?

Nations is a non-profit that reaches out to indigenous youth through skateboarding. The squad consists of myself, Rose Archie, Dustin Henry, Tristan Henry and Adam George. Our first gig was going to Fort St. John in northern BC. Vans was on board and gave us 50 pairs of shoes and we had a non-profit here that helped us out with some set-ups. We had 44 kids up there and each one of them got a set-up and a pair of shoes. When those kids came in, none of them had ever stepped on a skateboard. When we were done they were lining up to drop in on the quarterpipe. That’s how quick they took to it. It got to the point where our job was done. These kids are legit just shredding now.

How do you feel about the current state of indigenous skateboarding?

I feel like it is at an all-time high because of the popularity of skateboarding right now. Back when I started, indigenous/First Nations skaters were few and far between and I didn’t even know a scene existed anywhere else. One exception was Sam Devlin who had a part in Trilogy. Back in the day you could get your ass kicked just for having a skateboard anywhere you went. You were labeled an outcast. Now everyone and their dog skateboards, and I’ll bet that it is only going to continue to grow from here.

For more info check: @nationskateyouth

This short documentary below is a powerful tribute Joe Buffalo.

-

7/20/2023

The Follow Up: Joe Buffalo

From early success, to death’s door and back, Joe Buffalo is as resilient as he is powerful in the streets. Read up as he talks us through the fasting and manifesting of a Sundance ceremony and how his new Antihero board confronts Canada’s RCMP head on. -

8/03/2021

Menu Skate Shop's "M E N U" Video

Jess Wong brings to life a vision of Vancouver with Joe Buffalo, Tom Robinson, Aleka Lang and more from the Menu crew. Play this one back a few times. -

4/08/2021

Alltimers' "ET&DUSTIN" Video

Dustin’s tasteful manuals and Etienne’s effortless flow compliment each other in this well-orchestrated back and forth from the North.